This article aims to provide a comprehensive guide to understanding and resolving race conditions in Golang applications. It starts with an introduction to race conditions, explaining what they are and why they are problematic, accompanied by real-world examples. The article then moves on to identifying race conditions in Golang, detailing the tools and techniques such as the Go race detector and common signs of race conditions in your code. It also explores the common causes of race conditions, including issues related to shared variables, improper use of goroutines, and synchronization problems, with illustrative code snippets. The article offers strategies to prevent race conditions, discussing the use of synchronization primitives like mutexes, channels, and atomic operations. For existing race conditions, a step-by-step guide is provided to resolve them, including how to refactor code and validate fixes using the Go race detector. To ensure robust concurrent programming, the article concludes with best practices, design patterns, and testing strategies. Finally, a summary of key points and additional resources for further learning are provided.

Understanding Race Conditions with Golang Applications

Race conditions are a common issue in concurrent programming, where two or more threads or processes access shared data and try to change it at the same time. This can lead to unpredictable behavior and bugs that are notoriously difficult to reproduce and diagnose. In this section, we’ll introduce the concept of race conditions, explain why they are problematic, and provide real-world examples of how they can manifest in software applications, particularly in Golang.

What is a Race Condition?

A race condition occurs when the outcome of a program depends on the sequence or timing of uncontrollable events such as thread scheduling. Specifically, if multiple threads or goroutines read and write shared data without proper synchronization, the final state of the data can vary depending on the timing of these operations. This can lead to inconsistent results, data corruption, and other unexpected behaviors.

Why Are Race Conditions Problematic?

Race conditions can be problematic for several reasons:

- Unpredictability: The non-deterministic nature of race conditions makes them difficult to reproduce and debug. A program may work correctly most of the time but fail under certain conditions.

- Data Corruption: Concurrent writes to shared data can corrupt the data, leading to incorrect program behavior and potential crashes.

- Security Vulnerabilities: Race conditions can introduce security vulnerabilities by allowing unauthorized access or modification of data.

Real-World Examples in Golang

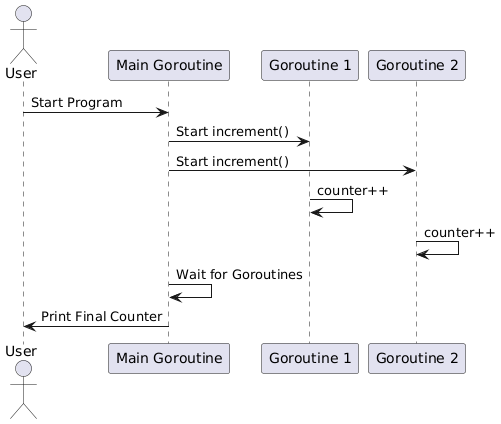

Let’s consider a simple example in Golang to illustrate a race condition. Suppose we have a counter that is incremented by multiple goroutines:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

)

var counter int

var wg sync.WaitGroup

func increment() {

defer wg.Done()

for i := 0; i < 10000; i++ {

counter++

}

}

func main() {

wg.Add(2)

go increment()

go increment()

wg.Wait()

fmt.Println("Final Counter:", counter)

}

In this example, we have two goroutines running the increment function, which increments a shared counter variable. The expected final value of counter should be 20000, but due to the race condition, the actual value may be less than 20000.

To observe the race condition, we can run the program multiple times and notice the varying output:

$ go run main.go

Final Counter: 15809

$ go run main.go

Final Counter: 20000

$ go run main.go

Final Counter: 16618

As seen, the final value of counter is inconsistent, indicating a race condition.

In the next sections, we’ll explore synchronization mechanisms available in Golang to address race conditions, delve into the impact on performance, and discuss best practices to prevent these issues.

Identifying Race Conditions in Golang

Before you can fix race conditions, you need to identify them. In this section, we will cover the tools and techniques for detecting race conditions in Golang applications. We will discuss the Go race detector, how to enable it, and interpret its output. Additionally, we’ll look at common signs of race conditions in your code, such as unexpected behaviors and intermittent bugs.

The Go Race Detector

The Go race detector is an invaluable tool for identifying race conditions in your code. It works by dynamically analyzing your program to detect concurrent access to shared variables, where at least one access is a write. When a race condition is detected, the race detector provides detailed information about the conflicting accesses.

Enabling the Race Detector

To enable the race detector, you need to use the -race flag when running or testing your Go application. Here’s how you can do it:

go run -race main.go

For testing purposes, you can enable the race detector as follows:

go test -race ./...

Interpreting Race Detector Output

When the race detector identifies a race condition, it outputs a detailed report that includes the following information:

- Goroutine Stack Trace: The stack traces of the goroutines involved in the race condition.

- Source Code Location: The exact lines of code where the conflicting accesses occurred.

- Access Types: Whether the conflicting accesses are reads or writes.

Here is an example of what the race detector output might look like:

==================

WARNING: DATA RACE

Read at 0x00c0000b4010 by goroutine 6:

main.readCounter()

/path/to/main.go:15 +0x3c

Previous write at 0x00c0000b4010 by goroutine 7:

main.incrementCounter()

/path/to/main.go:10 +0x3e

Goroutine 6 (running) created at:

main.main()

/path/to/main.go:20 +0x58

Goroutine 7 (running) created at:

main.main()

/path/to/main.go:21 +0x68

==================

In this example, the race detector has identified a data race between a read operation in readCounter and a write operation in incrementCounter.

Common Signs of Race Conditions

Race conditions can manifest in various ways, often making them difficult to diagnose. Here are some common signs that your code might have a race condition:

- Intermittent Bugs: Bugs that occur sporadically and are hard to reproduce consistently.

- Unexpected Behavior: Program behavior that deviates from the expected outcome, especially under concurrent execution.

- Crashes and Panics: Sudden crashes or panics that occur without a clear cause, often due to corrupted state.

Example: Detecting a Race Condition

Let’s consider a simple example to illustrate how you might detect a race condition using the Go race detector.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

)

var counter int

func increment(wg *sync.WaitGroup) {

defer wg.Done()

for i := 0; i < 1000; i++ {

counter++

}

}

func main() {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

wg.Add(2)

go increment(&wg)

go increment(&wg)

wg.Wait()

fmt.Println("Final Counter:", counter)

}

To detect a race condition in this code, run it with the race detector enabled:

go run -race main.go

The race detector will report a data race between the two goroutines accessing the counter variable concurrently.

By understanding how to use the Go race detector and recognizing the signs of race conditions, you can more effectively identify and address these issues in your Golang applications. In the next sections, we will explore techniques for resolving race conditions, including the use of mutexes, atomic operations, and concurrency patterns.

Common Causes of Race Conditions in Golang

Understanding the root causes of race conditions is crucial for preventing them. In this section, we’ll delve into the common causes of race conditions in Golang applications. We’ll explore issues related to shared variables, improper use of goroutines, and synchronization problems. Each cause will be illustrated with code snippets and detailed explanations.

Shared Variables

One of the most common causes of race conditions is the improper handling of shared variables. When multiple goroutines access and modify the same variable concurrently without proper synchronization, it can lead to unpredictable behavior.

Example:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

)

func main() {

var counter int

var wg sync.WaitGroup

for i := 0; i < 1000; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

counter++

}()

}

wg.Wait()

fmt.Println("Counter:", counter)

}

In the above example, multiple goroutines are incrementing the counter variable concurrently. This can result in a race condition, leading to an incorrect final value of counter.

Improper Use of Goroutines

Goroutines are lightweight threads managed by the Go runtime. While they are powerful, improper use can lead to race conditions. For example, launching goroutines without proper synchronization mechanisms can cause data races.

Example:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

go func(i int) {

fmt.Println(i)

}(i)

}

time.Sleep(1 * time.Second)

}

In this example, the goroutines print the value of i. Due to the lack of synchronization, the output can be unpredictable, as the value of i may change before the goroutine executes.

Strategies to Prevent Race Conditions

Prevention is better than cure, especially when it comes to race conditions. This section will outline various strategies to prevent race conditions in Golang. We’ll discuss the use of synchronization primitives such as mutexes, channels, and atomic operations. Practical examples and best practices will be provided to help you write safer concurrent code.

Using Mutexes

Mutexes are one of the most common synchronization primitives used to prevent race conditions. They work by locking a shared resource, ensuring that only one goroutine can access it at a time. In Golang, you can use sync.Mutex and sync.RWMutex for this purpose.

Example with sync.Mutex:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

)

func main() {

var counter int

var mu sync.Mutex

var wg sync.WaitGroup

for i := 0; i < 1000; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

mu.Lock()

counter++

mu.Unlock()

}()

}

wg.Wait()

fmt.Println("Counter:", counter)

}

In this example, mu.Lock() and mu.Unlock() ensure that only one goroutine can increment the counter at a time.

Example with sync.RWMutex:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

)

func main() {

var counter int

var mu sync.RWMutex

var wg sync.WaitGroup

// Writer

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

mu.Lock()

counter++

mu.Unlock()

}()

// Reader

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

mu.RLock()

fmt.Println("Counter:", counter)

mu.RUnlock()

}()

wg.Wait()

}

Here, sync.RWMutex allows multiple readers to access the counter concurrently, but only one writer at a time.

Using Channels

Channels provide a way to synchronize goroutines and prevent race conditions by ensuring only one goroutine accesses shared data at a time. They are particularly useful for communication between goroutines.

Example:

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func main() {

ch := make(chan int)

go func() {

ch <- 42

}()

value := <-ch

fmt.Println(value) // Output: 42

}

In this example, the channel ensures that the value 42 is safely passed from one goroutine to another.

Using Atomic Operations

Atomic operations are provided by the sync/atomic package in Go. They allow for safe atomic increments and other operations without the need for mutexes.

Example:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync/atomic"

)

func main() {

var counter int32 = 0

atomic.AddInt32(&counter, 1)

fmt.Println(counter) // Output: 1

}

Atomic operations ensure that the increment operation is performed atomically, preventing race conditions.

Best Practices

- Minimize Shared State: The less shared state you have, the fewer opportunities there are for race conditions.

- Use Higher-Level Abstractions: Whenever possible, use higher-level abstractions like channels instead of low-level synchronization primitives.

- Consistent Locking Order: Always acquire locks in a consistent order to prevent deadlocks.

- Limit Scope of Locks: Keep the scope of locks as small as possible to minimize contention.

- Profile and Test: Use tools like the Go race detector to profile and test your code for race conditions.

By understanding and implementing these strategies, you can effectively prevent race conditions in your Golang applications.

Resolving Existing Race Conditions

When you already have a race condition in your code, it can be daunting to identify and resolve it efficiently. This section will provide a step-by-step guide to addressing existing race conditions in Golang applications. We’ll cover how to refactor your code, implement proper synchronization, and validate the fixes using the Go race detector. Additionally, we’ll include real-world case studies to illustrate the resolution process.

Step-by-Step Guide to Resolving Race Conditions

Step 1: Identify the Race Condition

The first step in resolving a race condition is identifying where it occurs. The Go race detector is a powerful tool for this purpose. You can run your tests with the -race flag to detect any race conditions in your code.

go test -race ./...

When the race detector identifies a race condition, it will provide detailed information about the conflicting accesses, including the goroutines involved and the specific lines of code.

Step 2: Analyze the Problematic Code

Once you’ve identified the race condition, the next step is to analyze the problematic code. Look for shared resources that are being accessed concurrently without proper synchronization. Common culprits include global variables, shared structs, and slices.

Step 3: Refactor to Implement Proper Synchronization

After identifying the shared resources causing the race condition, you need to refactor your code to implement proper synchronization. Depending on your use case, you might use mutexes, channels, or atomic operations.

Step 4: Validate the Fixes

After refactoring your code to implement proper synchronization, you need to validate the fixes using the Go race detector. Run your tests again with the -race flag to ensure that the race conditions have been resolved.

go test -race ./...

If the race detector does not report any race conditions, your fixes are likely successful. However, it’s essential to conduct thorough testing to ensure that all edge cases are covered.

Best Practices for Concurrent Programming in Golang

To wrap up, this section will offer best practices for concurrent programming in Golang to help you avoid race conditions and other concurrency issues. We’ll discuss design patterns, code reviews, and testing strategies that can make your concurrent code more robust and maintainable. By following these best practices, you can write high-performance, concurrent Golang applications with confidence.

Design Patterns for Concurrency

-

Worker Pools: Using worker pools can help manage the execution of multiple tasks concurrently. This pattern involves creating a pool of worker goroutines that process tasks from a shared channel.

package main import ( "fmt" "sync" ) func worker(id int, tasks <-chan int, wg *sync.WaitGroup) { defer wg.Done() for task := range tasks { fmt.Printf("Worker %d processing task %d\n", id, task) } } func main() { const numWorkers = 3 tasks := make(chan int, 10) var wg sync.WaitGroup for w := 1; w <= numWorkers; w++ { wg.Add(1) go worker(w, tasks, &wg) } for t := 1; t <= 10; t++ { tasks <- t } close(tasks) wg.Wait() } -

Pipeline Pattern: This pattern involves passing data through a series of stages where each stage performs a specific transformation or processing step. Each stage is typically a goroutine that reads from an input channel and writes to an output channel.

package main import "fmt" func generator(nums ...int) <-chan int { out := make(chan int) go func() { for _, n := range nums { out <- n } close(out) }() return out } func square(in <-chan int) <-chan int { out := make(chan int) go func() { for n := range in { out <- n * n } close(out) }() return out } func main() { in := generator(2, 3, 4) out := square(in) for result := range out { fmt.Println(result) } }

Testing Strategies

-

Unit Testing: Write unit tests for individual components of your concurrent code. Use the

testingpackage to create test cases that cover both normal and edge cases.package main import ( "testing" ) func TestAddSession(t *testing.T) { addSession("1", "data1") if getSession("1") != "data1" { t.Errorf("Expected 'data1', got '%s'", getSession("1")) } } -

Integration Testing: Perform integration testing to ensure that different parts of your application work together as expected. This is crucial for concurrent applications where interactions between components can introduce race conditions.

-

Race Detector: Always run your tests with the race detector enabled (

go test -race). This tool can help identify race conditions that might not be apparent during normal execution.go test -race ./... -

Stress Testing: Stress testing involves running your application under high load to identify performance bottlenecks and concurrency issues. Use tools like

pproffor profiling and identifying hotspots.import ( "net/http" _ "net/http/pprof" ) func main() { go func() { http.ListenAndServe("localhost:6060", nil) }() // Your application code here }

By adhering to these best practices, you can significantly reduce the likelihood of encountering race conditions and other concurrency issues in your Golang applications. Design patterns like worker pools and pipelines provide structured ways to manage concurrency, while thorough code reviews and testing strategies ensure that your code is robust and maintainable. Utilizing tools like the race detector and pprof can help you identify and resolve issues early, leading to high-performance, reliable applications.